Who Feed a Beef Burger to His Daughter in Mad Cow Disease

The 'Mad Cow Disease' Scandal

How the UK Government put millions at risk of a 100% fatal illness

It was just before Christmas 1984 when Cow 133 on Stent Farm in Sussex, England began to behave strangely. The cow's head was trembling and it had lost co-ordination. The cow died in February 1985 and was sent for autopsy. It was not until September that the result came back that the cow had died of the brain disorder spongiform encephalopathy. Over a year later, at the end of 1986, a new disease was acknowledged: Bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or BSE, commonly known as Mad Cow Disease.

It was just before Christmas 1984 when Cow 133 on Stent Farm in Sussex, England began to behave strangely. The cow's head was trembling and it had lost co-ordination. The cow died in February 1985 and was sent for autopsy. It was not until September that the result came back that the cow had died of the brain disorder spongiform encephalopathy. Over a year later, at the end of 1986, a new disease was acknowledged: Bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or BSE, commonly known as Mad Cow Disease.

As more and more cows in the UK fell ill, it was established that they had likely become infected with BSE after eating meat and bone meal — a type of cattle feed made from leftovers from animal carcasses, including cows. The cattle, naturally herbivores, had been consuming their own species.

In July 1988, the UK government banned meat and bone meal from cattle feed but, by then, an estimated one million cows infected with BSE had entered the human food chain.

It was assumed that BSE was not transmittable to humans. This was based on the fact that meat from sheep infected with a similar neurological disease — known as scrapie— had been eaten by humans for centuries with no discernible ill-effects.

Mechanically Recovered Meat

During the 1980s, mechanically recovered meat (MRM) from cow carcasses was used in foods such as sausages, burgers, and meat pies. MRM could contain cows' brain matter and spinal cords — the most infectious parts of a BSE-infected cow carcass. The public was unaware that their food contained this by-product.

School children were at particular risk of consuming BSE-infected MRM. In 1980, the UK's Conservative government — led by Margaret Thatcher — had removed the requirement for school lunches to have any nutritional value. Whatever was cheapest was what was served up by the private companies supplying school canteens, and products made from MRM could be up to 10x cheaper than other meat products.

By 1990, a whole generation of British children was being exposed to potentially contaminated beef — their fast food burgers, their Birthday party sausage rolls, their cheaply-made school dinners; all could potentially infect them.

Whilst school children faced more exposure to infected meat products, anyone eating British beef was also unknowingly putting themself at risk.

Beef is Safe

Despite the outbreak of BSE amongst British beef cattle, the Conservative government insisted that British beef was safe for everyone to eat.

Two dissenting voices were microbiologists Prof. Richard Lacey and Dr. Stephen Dealler. Both argued that BSE-infected beef may cause a fatal brain disorder known as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) in humans.

Lacey — an outspoken anti-establishment figure — had been arguing the dangers of BSE since at least 1988. The Professor called for the slaughter of six million British cattle, half the national herd. Dealler went on TV to warn of the dangers of infected beef, telling viewers "the British public have already eaten 1.5 million infected cattle." Both faced a backlash and Dealler was removed from his research lab and had to continue his work in his garage.

In June 1990, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, responding to France and West Germany banning British beef imports, declared in Parliament "British beef is safe."

The financial health of the multi-billion-pound beef industry was placed ahead of the health threat to the UK population.

Some Members of Parliament went so far as to eat British steak tartare (raw beef) on camera to 'prove' it was safe. One Conservative Member of Parliament— John Gummer, the Agricultural Minister — was filmed forcing his four-year-old daughter to take a bite of a burger from a burger van and then eating the burger himself and declaring it "absolutely delicious!"

The same month as this publicity stunt, in May 1990, a BSE-type illness was found to have killed Max, a Siamese cat that had been fed on beef. The disease had jumped species. That year, 15 more cats were found to have died of feline BSE. The disease was also discovered in fourteen other species. There were increasing fears — suppressed, denied, and played down by the Government — that BSE would also cross to humans.

Stephen Churchill

In August 1994, 18-year-old Stephen Churchill, of Devizes, Wiltshire crashed the car he was driving into an Army truck coming in the opposite direction. Stephen survived but the car — his Mum's Ford Fiesta — was a write-off. Stephen could not explain how he had come to swerve across the road and crash.

In the months following the collision, Stephen fell into a deep depression and quit school. In November, his Mum took him shopping and to a cafeteria. Afterwards she asked him if he'd enjoyed their day out. He didn't remember it.

With doctors insisting Stephen had depression, his parents could only watch helplessly as his condition worsened: by December he was struggling with physical co-ordination and could no longer sign his name. His parents pushed doctors for a different diagnosis and on February 13, 1995 they got it: Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), a very rare degenerative brain disease normally seen in old people.

In Stephen, however, the disease appeared to be progressing differently to 'regular' CJD — scientists were looking at a new, unseen before variant of the disease.

Just over two months after his diagnosis, on May 21, 1995, Stephen died aged 19. His was the first confirmed death in the UK from new variant CJD (vCJD).

It was not until almost a year after Stephen's death, in March 1996, that the Conservative government finally publicly admitted that eating British beef contaminated with BSE could cause vCJD in humans. This had been the fear since at least mid-1990.

Mere months before this admission, Health Secretary Stephen Dorrell had stated that there was "no conceivable risk" from eating British beef.

By the end of 1996, thirteen people had died from vCJD in the UK.

In November 1997, the BBC's Panorama broadcast an episode on vCJD. The programme featured mother of two Donna Fellowship, 34, who was in the late stages of vCJD — unable to move, eat, speak or respond. She died the month after the programme was broadcast, the 27th confirmed victim of this new disease.

The same programme showed footage of Pamela Beyless, whose memory and recall were akin to someone with mid-stage dementia. She was 22. She died in October 1998, one of five vCJD deaths linked to a butcher's in the village of Queniborough, Leicestershire.

As Panorama pointed out, vCJD was only killing people in the UK. There had been no confirmed cases anywhere else.

By the end of 1999 there had been 56 deaths from vCJD in the UK.

"I Gave Her Something Which Killed Her"

The year 2000 would see a peak in deaths from vCJD with 28 people dying. At the time there were fears that this number would keep rising.

The first death in 2000 was schoolgirl Claire McVey who died in January 2000, aged only 15. Her mother Annie, speaking to the BBC in 2019, laments that "I gave her something which killed her." As Claire got sicker, she became "more agitated, more demanding, more frightened." Her family could only watch helplessly as her condition worsened.

At the time, Claire was the youngest person recorded to have died from vCJD.

In May 2000, Sally Evans, age 20, died of vCJD seven months after giving birth to a daughter, Emily. Emily was born with brain damage and requires 24 hour care. Her Grandmother Jean, who has cared for Emily her whole life told the Mirror in 2018: "Government failures let mad cow disease into the human food chain, killing my daughter and brain-damaging my granddaughter."

By October 2000, there had been 80 confirmed vCJD deaths in the UK, with five victims suffering from but yet to die of the disease.

At the end of that month, Zoe Jefferies would die of vCJD aged only 14, making her the youngest known victim. She had first become ill in July 1998. "I really do think she has been murdered" her mother said at the time.

Joanne Gibb was only 13 when she started showing symptoms of vCJD in November 2000; "she became very aggressive and unable to control her moods" remembers her mother Janet. By February 2001, Joanne's "behavioural problems had lessened but she couldn't walk steadily, her speech was slurred and she didn't want to go to school because she couldn't write properly." Joanne was eventually diagnosed with vCJD in May 2001.

It was not until 2001 that the UK Government (now under Labour rather than the Conservatives) banned the sale of MRM beef for human consumption.

This belated action was far too late to stop the deaths from vCJD of those infected in the 1980s — 1990s. Joanne Gibb died on New Years Day 2003.

"Our Daughter was Going to Die"

Deaths of British young people born in the mid 1980s from vCJD continued into the mid 2000s.

Student Emma Wild died in March 2005, aged 21 after having been diagnosed the previous July. Her father, Nigel, told the Manchester Evening News in 2005: "At least with cancer you know there is a chance of a cure, but with CJD there is no cure. We had to face up to the fact that our daughter was going to die." Her mother Sharron said: "It's a man-made disease and should never have happened, the government just wants to push it under the carpet"

In October 2007, the Guardian revealed that the daughter of a friend of John Gummer, the Agricultural Minister filmed feeding a burger to his young daughter, had died of vCJD. Elizabeth Smith, aged 23, died after suffering from the disease for three years. She first became ill whilst studying at University and within weeks she was unable to move, talk or feed herself. "It was remorseless in the way it killed her off" remembers her father Roger.

After the number of vCJD deaths peaked in 2000, another 87 people were confirmed to have died of vCJD in the UK between 2000 and 2010. By 2010 deaths were down to three per year.

A Second Wave?

Based on the likely peak of human exposure to BSE in the UK (c. 1989–1990) and the peak in deaths from vCJD (in 2000), the estimated time from infection to death is around 10 years.

Whilst each vCJD death is a tragedy that could and should have been prevented, the rate of death is (so far) mercifully small.

The European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) records that, as of January 2015, there have been 226 confirmed deaths from vCJD worldwide, of which 177 or 78% occurred in the UK.

Of those who have died from vCJD (100% of those diagnosed), 184 or 81% had lived in the UK for more than six months between 1980 and 1996. So far, all vCJD cases have occurred in people born in 1989 or earlier.

But could we experience a second wave of vCJD cases?

According to the ECDC, up until 2015 all those who have died from vCJD have had a specific genotype. If people with a different genotype are not immune but are in fact infected with so-far dormant vCJD "subsequent epidemics…may yet appear."

Not included in the ECDC's figures is the most recent UK death from vCJD, which occurred in 2016. This death was unusual as the 36-year-old victim had a different genotype to all previous confirmed victims. His death may signal that a 'second wave' of deaths is imminent among those with this other genotype — amongst people who are infected with vCJD but whose infections have lain dormant so far. Fifty one percent of the UK population has this other genotype.

There is no one known to be living with active vCJD in the UK as at January 10, 2022.

Cases Missed?

In January 2017, an article in the New Scientist argued that cases of so-called sporadic CJD (also fatal) may in fact instead have been vCJD (i.e CJD caused by consuming BSE infected beef). The number of cases of sporadic CJD has climbed from 85 in 2010 to 125 in 2021, with a peak of 137 cases in 2018.

According to the ECDC, it is possible that cases of death from vCJD in older people have also been missed as vCJD can only be confirmed via post mortem examination of the brain, which is rare in cases of older people dying from what appears to be dementia.

Bad Blood

vCJD is present not only in an infected person's brain but also in their blood, specifically in their white blood cells.

When someone is diagnosed with vCJD, their medical records are checked to see if they have ever donated blood.

By 2004, four people who had received blood transfusions traced back to donors who later died of vCJD, had also themselves died of vCJD, though we cannot be one hundred percent certain that they contracted vCJD from these blood transfusions.

Many countries, for example EU countries such as France, Spain, and Germany have banned donations of blood by anyone who spent more than a year total in the UK between 1980 and 1996.

The USA, Canada and Australia have banned donations of blood by anyone who spent three — six months or more in the UK between 1980 and 1996, millions of people in total.

Despite serious blood donation shortages in these countries, blood donation services remain extremely cautious even almost 30 after the first vCJD deaths. There is no test to see if donated blood is infected with vCJD so, to be safe, all donation is banned.

"They Were the Government and We Trusted Them"

In 2013, a peer-reviewed scientific study estimated that one in every 2,000 people in the UK may be a carrier of vCJD.

There is still no test, effective treatment, or cure for vCJD.

Scottish engineer Grant Goodwin died of vCJD in 2009 age 30. His mother Margaret remembers that when shopping for meat to feed her children "We just bought what we could afford." She didn't think these cheap meat products would be deadly, she had heard those in power say they were safe: "They were the Government and we trusted them."

Grant's father Tommy is unequivocal: his son was "murdered by greed and corruption."

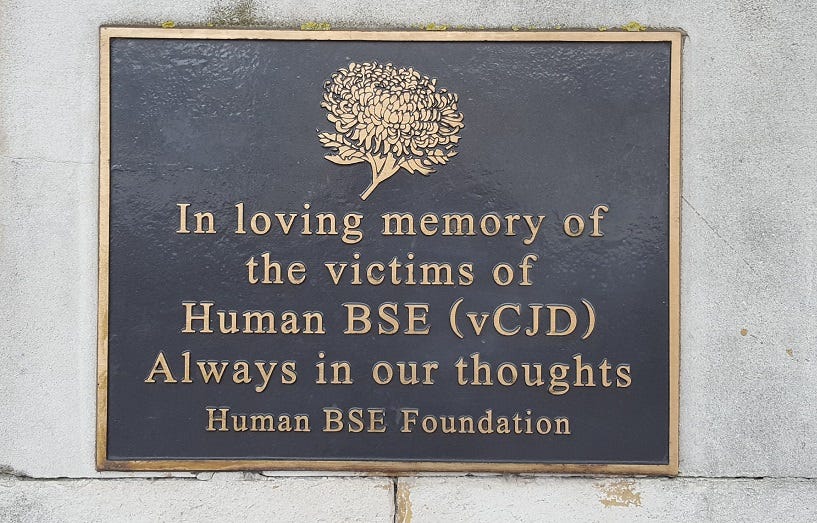

"Somehow, you can come to terms with losing someone through an accident or a natural disease" explains Francis Hall, founder of the Human BSE Foundation, but families who have lost someone to vCJD "feel their child has been murdered, yet nobody is going to be punished or even apologise." Hall's son Peter died from vCJD in February 1996 aged 20.

Every Christmas, Annie McVey sends a photo of her dead daughter Claire along with an email to various people in positions of power. The email reads:

"You did this. When you sit down to your Christmas lunch, we sit down to an empty space. Because of the choices you made. So when you make your next choice in parliament or in business, make sure it's a good one. Because they have consequences."

In 2000, former Health Secretary Stephen Dorrell said that he "regretted" having told the British public in 1996 that there was "no risk" from eating British beef. He is no longer a Member of Parliament.

John Gummer, the burger-munching Minister for Agriculture during the BSE outbreak, now sits in the House of Lords as Lord Debin.

Additional Source

BBC, 2019, Mad Cow Disease: The Great British Beef Scandal (documentary).

BBC, 1997, Panorama: The British Disease (documentary).

Any information not referenced above comes from these two documentaries.

Source: https://historyofyesterday.com/the-mad-cow-disease-scandal-8d1665af2dc9

0 Response to "Who Feed a Beef Burger to His Daughter in Mad Cow Disease"

Post a Comment